Golden Minerals Company

Unfortunately this article is 3 years old and none of its ideas have been implemented:

Robin Hood was a thief not a saviour

I quite liked Robin Hood on TV when I was young. After each episode, there were famous sword duals in backyards, with usually some oppressive older brother playing the role of the sheriff and the youngest least defenceless kids were “his men”. The rest of us were the outlaws and we hid in bushes and sharpened dangerous bits of wood and fired them from powerful home made bows at the oppressors. Mothers had first-aid kits constantly in use. Neighbourhood girls were usually attracted to the outlaws which was always a useful by-product that the sheriff and his “men” seemed to overlook, although most of the “men” were too young to gauge the significance of this. Yes, 1960s suburban Australia. Anyway, Robin is back in town but this time some do-gooders are invoking his name to solve the problems of the world. However, none of their “solutions” are viable and are based on faulty understandings of the way monetary systems operate.

I last wrote about the concept of a Tobin tax in this blog – A global financial tax? – and I would read that in addition to this blog for a full view of what Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) position might be.

Anyway, there is gathering support for an excise to be levied on financial transactions. Part of the push is coming from an increasing awareness that short-termism or high frequency trading is now becoming dominant in global financial markets.

The UK-based Robin Hood Tax group have published a very interesting paper – Financial Transaction Taxes: Tools for Progressive Taxation and Improving Market Behaviour – which attempts to trace through the incidence of the tax.

The Robin Hood report summarises some salient (sourced) facts of trends in global financial markets:

- “High frequency traders now account for 70% of US equity market trading volume and account for between 30%-40% of the trading volume at the London Stock Exchange”.

- “High frequency traders reportedly account for 50% of US future market volume, 25% of foreign exchange volume are becoming increasingly important in options markets”.

- “Banks account for only 13% of the trading volume at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange one of the largest and most diversified exchanges in the world trading in commodity, equity, energy, forex, interest rate, metals, real estate and weather products. Much of the balance is attributable to hedge funds”.

- “Hedge funds represent more than 30% of the volume in high yield debt, 90% in convertible bonds, almost 90% of distressed debt and emerging market debt”.

- “Hedge funds are the dominant players in the credit default swap market accounting for more than 60% of market volume”.

- “Hedge funds are responsible for between 55% and 60% of transactions in leveraged loans”.

High-frequency trades are driven by algorithms automatically programmed to follow rules that can generate a multitude of (usually small) trades per second.

The Robin Hood report notes that:

In surveys of traders in foreign exchange markets, two thirds of them say that for time horizons of up to six months, economic fundamentals are not the most important determinant of trading prices. Instead they point to speculation, herding and ‘technical trading’.

An interesting insight into the way in which financial markets have evolved was provided by the US-based Aspen Institute in their policy document – Overcoming short-termism – which was released in September 2009.

They argue that even from a corporate perspective, short-termism in financial markets is broadly damaging. It said that:

… high rates of portfolio turnover harm ultimate investors’ returns, since the costs associated with frequent trading can significantly erode gains.

… fund managers with a primary focus on short-term trading gains have little reason to care about long-term corporate performance or externalities, and so are unlikely to exercise a positive role in promoting corporate policies, including appropriate proxy voting and corporate governance policies, that are beneficial and sustainable in the long-term …

… the focus of some short-term investors on quarterly earnings and other short-term metrics can harm the interests of shareholders seeking long-term growth and sustainable earnings, if managers and boards pursue strategies simply to satisfy those short-term investors. This, in turn, may put a corporation’s future at risk.

They recommended an excise tax be levied on financial transactions to discourage short-term strategies.

So the Robin Hood movement is correct in being motivated to curb this mindless and unproductive behaviour but imposing a tax is, in my opinion, not the way to go. More about which later.

The topic has received national attention in Australia in the last week. On the ABC national radio current affairs program PM the other day (March 30, 2010) they ran a story Aussies campaign for Robin Hood tax and a derivative article from the journalist Stephen Long was entitled – Robin Hood tax ‘could feed millions’.

The last title is telling because it demonstrates how we focus on financial dimensions when we should be considering real dimensions. It is food that feeds people not “revenue”. I will explain as I go.

The story demonstrated two fundamental things. First, those who mean-well should understand the way monetary systems operate before running spurious campaigns. Two, conservatives who claim to be experts on financial systems lie.

Neither is very helpful in attempting to unravel the complexities of the issues being discussed.

The ill-informed

The next quote is from the transcript of the radio segment. The interview is between journalist Stephen Long and well-known philosopher Peter Singer, who is no monetary theorist. He is progressive on ethics issues but plays into the hands of the mainstream economists in his sortie into monetary theory and policy. Long is speaking first and is summing up the message from the video that the UK Guardian is offering on Tobin Taxes featuring actor Bill Nighy.

Advocates say the tiny tax would raise hundreds of billions of dollars to combat global warming, reduce poverty and repair the battered finances of governments after the GFC.

(YouTube excerpt)

ACTOR: So let me get this clear, a tiny tax on the banks could raise billions of pounds every year to help save lives in the poorest countries, fund crucial action against climate change around the world and help avoid cuts to crucial public services in this country?

BILLY NIGHY: Gosh, well, yeah, that, that is about the um, um sum of it.

PETER SINGER: Look we’re talking about a really tiny tax. We’re talking about, not 1 per cent, not a 10th of 1 percent, but a 20th of 1 per cent.

STEPHEN LONG: The ethicist, Peter Singer, is among a number of prominent Australians who have joined the global campaign.

PETER SINGER: Obviously I’m most interested in the fact that it can raise funds from all the world to help the world’s poorest people and to help pay for the damage that we’re doing to them through climate change.

But there’s also an economic argument, that it will reduce the volatility of international markets. That is, instead of huge billions of dollars being thrown around the world for a few moments here and there to earn a tiny profit, a very, very small tax would have an inhibiting effect on that.

So misconception is at the heart of Singer’s major interest – raising “funds from all the world to help the world’s poorest people”. The intent is clearly sound notwithstanding the trends in modern development economics at present where people like Dambisa Moyo and Bill Easterly eschew aid to less developed countries. I am very critical of their arguments but will leave that for another time.

There are two separate points here. First, if you think the high income earners have too much purchasing power then a tax is one way of reducing that. Second, if you think that the low or no income earners have too little purchasing power then you can address that directly with government spending. I prefer spending that generates employment for those who are without jobs as the first step.

Further, if you think that it is the responsibility of the high income earners to feed the low or no income earners then you should say that at the outset. But the argument is rarely presented in this way. It is always presented as a scarcity of financial means and so the “high income earners” are the only source of “spare cash” because they have so much. It is an argument that is somewhat fraught.

Additionally, if you think that the government is the primary vehicle for improving the lot of the world’s poorest people, which is underpinning these proposals, then you don’t have to tax anyone to help the world’s poorest people.

MMT shows us clearly that sovereign governments have the capacity to eliminate poverty with one keystroke on their spending terminal without recourse to “funding” should they be motivated to do so and should there be enough real resources available such that the spending can be “effective”.

Effective means that the spending actually can purchase real goods and services that will be suitable for the purpose. This is an essential aspect of what I term fiscal sustainability – if a government wants to advance public purpose – and that should be its only goal – then it cannot just spend wastefully and advantage power elites.

So while public purpose requires the governments to sustain adequate levels of aggregate demand such that everyone can get a job at decent pay (even if some can only work at the minimum wage), it also requires attention to the form that the aggregate demand support takes.

As an aside, a topical example of where stimulus support is not sound is the current emerging issue in Australia about the Schools’ Building Program. Despite the government’s claims to the contrary, it has actually been paying significant (read: exorbitant) fees to construction companies to ensure projects were fast-tracked under its capital works’ stimulus program. The payments have clearly gone into the coffers of huge and wealthy corporates which has reduced the social return flowing to the rest of us.

Anyway, back to feeding the poor. The alternative scenario, which is not often rehearsed in these Robin Hood suggestions is that there might not actually be enough food to go around. I am using the descriptor “food” liberally here given our discussion recently about the state of food provision in advanced countries which is controlled by huge multinational corporations. One might forgive the statistician if they allocated food production to the plastics industry output results in this context.

But if you think that there is not enough food available overall to provide adequate nutrition to all the world’s citizens then you do have to redistribute real resources to avoid introducing inflationary pressures. Taxes are good vehicles for achieving this end. But would a Tobin Tax be the best tax instrument in this regard – I think not. For a start, what will be the incidence?

Economists use the term tax incidence to describe who ultimately “bears the burden of the tax”:

The key concept is that the tax incidence or tax burden does not depend on where the revenue is collected, but on the price elasticity of demand and price elasticity of supply. For example, a tax on apple farmers might actually be paid by owners of agricultural land or consumers of apples.

Who bears the incidence is complex but I doubt that Lloyd Blankfein will personally lose very much as a result of the tax. The cost will be shifted to those who use the financial products.

The Robin Hood paper noted above, attempts to trace through the incidence of a Tobin tax. They conclude:

Based on this analysis the final incidence of financial transaction taxes will fall on a number of actors, in particular

- High net worth individuals invested in hedge funds

- Employees of hedge funds

- Shareholders of investment banks

- Employees of investment banksA much smaller burden of the taxes would fall on

- Institutional investors such as pension funds

- Corporate and retail users of financial services

This is an issue that needs more research.

However, if there isn’t enough food to go around, then this is not a Robin Hood exercise based on a lack of financial capacity. It is a straight-forward exercise of depriving access to real goods (food) for some (the high income earners) in order to give that same food (given the shortage) to the poor who would otherwise (and do) go without.

I also think the terminology is unclear. Robin of Locksley stole from the rich to give to the poor and garnered support, so the TV series taught me, because of the perceptions of the common-folk and some of the nobility, that the monarchical system at the time was oppressive and evil. So stealing was considered a “just” response to oppression.

I sense that a lot of the do-gooders now are feeling similar things but the Sheriff and his mean are the bankers and the Tobin Tax represents the merry men of Sherwood.

Popular emotions are hardly the basis for sustainable economic policy and in that sense I think we should not be thinking in Robin Hood terms. If we think the bankers are worthy of an assault then lets devise an economic policy response that gets to the nub of the issue.

The MMT solution does this. It clearly delineates (in concept) financial (speculative) behaviour that assists international trade in real goods and services – so counter-parties which allow a trading firm to hedge foreign exchange exposure.

But then the question that is begged in discussions about the Tobin Tax is: why do we want to allow these destabilising financial flows anyway? If they are not facilitating the production and movement of real goods and services what public purpose do they serve?

The answer is they serve no useful purpose. They clearly have made a small number of people fabulously wealthy. They have also damaged the prospects for disadvantaged workers in many less developed countries.

More obvious to all of us now, when the system comes unstuck through the complexity of these transactions and the impossibility of correctly pricing risk, the real economies across the globe suffer. The consequences have been devastating in terms of lost employment and income and lost wealth.

The correct policy response is the make these unproductive transactions illegal. There is no need to gain revenue from them.

If the aim of the tax is to create disincentives for the high-frequency trades then why not just make it illegal.

The deceivers …

The ABS program also interviewed one Sam Wylie who is a senior fellow at the Melbourne Business School and claims to be an expert in financial matters. He told the interviewer that he was against a Tobin tax because “(i)t has the potential to do quite a lot of damage and very little good”.

The interview went like this, with Wylie initially referring to some of the prominent Australians who are calling for the Tobin Tax:

SAM WYLIE: Well, there’s certainly some great people involved. I know that Tim Costello and, and Peter Singer, for instance are tremendous Australians and powerful intellects promoting this idea. But they’re not finance people. You know, they’re great in their, in their own fields but I really feel that they don’t understand the complexity of the modern financial system …

Well, you know, most of what’s going on in transactions in financial markets is hedging and not speculation. If you’re a company like Qantas, Qantas faces a, a lot of risk associated with the oil price and so they put in place a set of hedges to, to control the oil price risk that they face.

You know a Tobin tax says if you want to adjust your hedging position, you have to pay for that. A Tobin tax says to National Australia Bank who, who borrow money overseas in US dollars, bring it to Australia and lend it to Australian households to build and buy houses, if you want to hedge your foreign exchange risk, which they simply have to do, if you want to change your hedging position, you have to pay for that.

So it actually has the potential to do a lot of damage. People think that most of what’s going on in, in these transactions is really to do with wild speculation. But that’s just not right.

Well it is clear that Tim Costello and Peter Singer are not finance people as noted above. But Wylie – by his own words is holding himself out to the public as a person who does “understand the complexity of the modern financial system” is totally deceiving the audience with spurious information.

Either he doesn’t know what he is talking about or he has deliberately mislead the public in trying to say that the financial markets are all about supporting trading in real goods and services.

The data shows (Source) that “the volume of foreign exchange transactions is almost 70 times higher than world trade of goods and services”. Further:

In Germany, the UK and the US, the volume of stock trading is almost 100 times bigger than business investment, and the trading volume of interest rate securities is even several 100 times greater than overall investment.

Whichever way you want to interpret the data, Wylie is completely wrong. The vast majority of cross-border financial transactions do not support trade in real goods and services.

Fortunately, Stephen Long the journalist who put this story together for the ABC also interviewed an “expert on banking and finance law and policy” from UNSW, Professor Ross Buckley, who challenged Wylie:

ROSS BUCKLEY: Well, that’s simply not true. I mean nobody hedges for two seconds, right? Nobody hedges for nanoseconds …

You know a substantial proportion of transactions in modern financial markets are for less than a second. The asset is bought, held and sold. The total time period is less than a second. That’s not a hedge, that’s a gamble, like at the race track.

Wylie should resign immediately or be sacked.

Digression: Was there a recession in Australia?

The Australian Bureau of Statistics began publishing their Job Vacancies data again today after suspending its collection over 2008/09 as a result of cuts to their budget by the incoming federal government. The latter, if you recall (or don’t as the case may be), came into power in November 2007 all geed up with neo-liberal zeal that they were going to run a bigger surplus that the conservatives and therefore prove they were more responsible.

Their number one enemy at the time was inflation and they claimed that a larger surplus would help fight it. So where better to start cutting spending than to reduce the quality of the data collection capacity of the national statistician. It was a total joke. Among other problems this stupidity caused was that the sample for the labour force survey was decreased which rendered almost all the regional level data useless. A related issue was that the ABS stopped collecting job vacancy information.

Anyway, by early 2008, the economic crisis has hit and Australia looked like going the way of the rest of the World and eventually as part of the stimulus packages the ABS had their budget restored enough to increase the labour force sample and to reinstate the Job Vacancies Survey. A major tick for fiscal stimulus!

However, as the ABS tell us today:

This is the first issue of Job Vacancies, Australia since May 2008 due to the suspension of the Job Vacancies Survey (JVS) in 2008/2009.

Caution should be used when comparing estimates from November 2009 onwards with estimates for May 2008 and previous periods, due to the changes outlined below.

To overcome the missing observations, I have done what I guess most users of the data will do and interpolate the 5 missing quarters between August 2008 and August 2009. The result doesn’t look to be in violating to what happened given that the suspension came just about at what would have been the turning point in the labour market anyway.

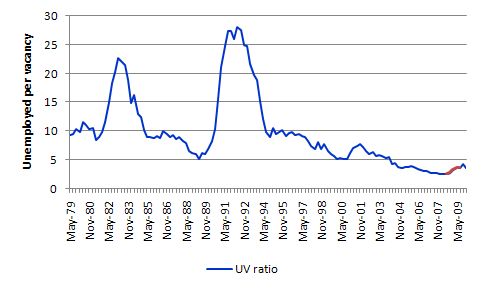

But when you plot the Unemployment to Vacancy ratio, which has been a popular measure of the “tightness” of the labour market (higher ratios = looser labour markets) the last year of so doesn’t look at all like our previous two recessions covered by the data (which starts in May 1979) in 1982 and 1991. The following graph is provided for interest (the red segment is where I interpolated the unavailable vacancy data).

So scholars in the future who didn’t live through this period would be excused for concluding that there wasn’t much of a downturn at all in Australia in the 2008-10. They would be wrong because the UV chart is unemployed persons per unfilled vacancy. There has been a fundamental shift in the way the labour market operates since 1991 and now underemployment has emerged as being a major problem.

In the current recession, firms adjusted working hours downwards without the commensurate adjustment in persons employed. While this sort of hours adjustment is typically associated with labour hoarding (keeping skilled or overhead staff on full pay but shorter hours) the current experience was not of this ilk.

Instead, employers took advantage of the rising precariousness of work which in recent years was accelerated by the pernicious WorkChoices legislation introduced as the final act of bastard madness by the previous conservative government which made casualisation of the workforce easier to achieve. Accordingly, firms can now force shorter-time without pay onto workers and that is what they did.

The implications of this shift in labour market behaviour has wider research implications. As one who has done a lot of work in the Phillips curve area (estimating wage and price adjustment functions) I now have to rethink that. In fact, we are working on a new model where the labour market tightness variable is broader. I published work on this about 5 years ago as the trend was becoming obvious and found then that underemployment disciplines the wage inflation process in addition to unemployment. The latter effect at that stage was stronger and we are now investigating what the situation is five years later.

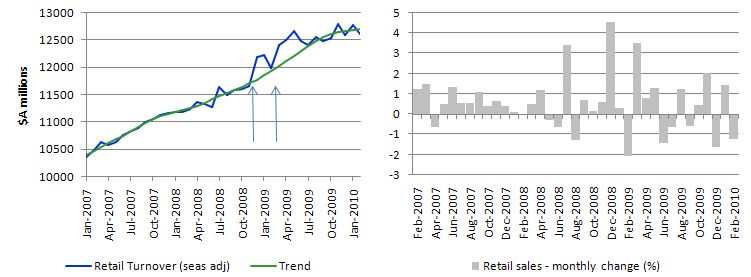

The other interesting data series released this week by the ABS (as mentioned yesterday) was the Retail Sales data for February 2010. It showed that the recent slow-down in retail sales has continued with a 1.4 per cent decline (seasonally-adjusted) for February following a 1.1 per cent increase in January 2010 and a 0.8 per cent decrease in December 2009.

Of all the data series that demonstrate the influence of the fiscal stimulus packages, this one is fairly categorical. Have a look at the graph below. The right-panel is the monthly percentage change in retail sales for Australia while the left-panel is the turnover in $A millions. The blue line in the left-panel is seasonally adjusted whereas the green line is the trend. The sample is from January 2007 to February 2010.

The blue arrows depict when the two stimulus packages came into force. The first in December 2008 provided consumers with a hand out of $900 unencumbered. The second announced large capital works outlays and helped increase the consumer sentiment indexes that are published. And as the fiscal impact dissipated retail sales the effect is very noticeable.

Conclusion

It would be futile to deter speculative behaviour that assists international trade in goods and services even though from a MMT perspective the benefits of trade are evaluated differently.

The other question that is begged by the discussions about the Tobin Tax is: why do we want to allow these destabilising financial flows anyway? If they are not facilitating the production and movement of real goods and services what public purpose do they serve?

It is clear they have made a small number of people fabulously wealthy. It is also clear that they have damaged the prospects for disadvantaged workers in many less developed countries.

More obvious to all of us now, when the system comes unstuck through the complexity of these transactions and the impossibility of correctly pricing risk, the real economies across the globe suffer. The consequences have been devastating in terms of lost employment and income and lost wealth.

So I don’t see any public purpose being served by allowing these trades to occur even if the imposition of the Tobin Tax (or something like it) might deter some of the volatility in exchange rates.

Solution: All governments should sign an agreement which would make all financial transactions that cannot be shown to facilitate trade in real good and services illegal. Simple as that. Speculative attacks on a nation’s currency would be judged in the same way as an armed invasion of the country – illegal.

This would smooth out the volatility in currencies and allow fiscal policy to pursue full employment and price stability without the destabilising external sector transactions.

Further, as noted above all the revenue arguments used to justify the Tobin tax are spurious when applied to a modern monetary system.

The proposal to declare wealth-shuffling of the sort targeted by a Tobin tax illegal sits well with the other financial and banking reforms I have discussed in these blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks .

That is enough for today!

22 Responses to Robin Hood was a thief not a saviour

-

Oliver says:

More obvious to all of us now, when the system comes unstuck through the complexity of these transactions and the impossibility of correctly pricing risk, the real economies across the globe suffer. The consequences have been devastating in terms of lost employment and income and lost wealth.

It seems the strategy many developed countries have been following is to loose that part of the economy which suffers most from such transactions (the real economy) and to keep that part which benefits most (finance) and then to buy back real produce from the ‘losers’ at low cost. The crisis has shown to everyone willing to look that hardly any of the wealth accumulated by this shift has trickled down to those talked into voting for it. But what you are asking for is that those countries who profited most in aggregate sign a contract that would ban their holy cash cow altogether. My political antenna tells me this (sensible adjustment) is highly unlikely. The Tobin Tax on the other hand seems a well-meant but feeble attempt to have it both ways.